Governments grapple with challenges of scarce supply and high costs in bid to cut carbon emissions

When one village resident wanted to join the green revolution by installing a heat pump in his English countryside home to replace an off-grid oil boiler, he had a frustrating year-long wait and paid a hefty bill.

Lord Adair Turner of Ecchinswell, the chair of the Energy Transition Commission and former UK government climate adviser, spends his professional life promoting the clean energy shift to the wider population.

“The most difficult challenge is figuring out how to enable millions of households to do what I’ve just done,” said Turner.

Governments across Europe are dealing with the same challenges of scarce supply and high costs in an effort to eliminate the burning of fossil fuels by gas central heating.

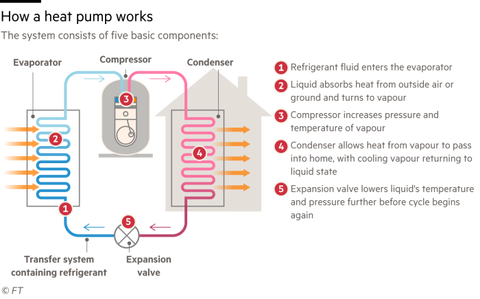

Heat pumps are a leading alternative, praised for their efficiency. Drawing warmth from the outside air or ground, they can produce 3kWh or more of heat for every kWh of electricity used to power them.

Yet the rollout is not as straightforward as that equation might suggest. Switching heating systems is costly and complicated for homeowners, holding back demand.

Workers assemble heat pumps at a factory in Eschenburg © Sascha Schuermann/Getty Images

Governments attempting to force the necessary change have not been rewarded, however.

Germany’s plans to in effect double heat pump sales are up in the air after a fierce backlash over a Green party proposal to ban gas and oil boilers, which has left the government in crisis.

“People call it the heating massacre,” said Alice Weidel, co-leader of the far right AfD party, after the proposed ban contributed to its first district election win, in Sonnenberg in June.

Just under 6 per cent of the 21mn heating systems installed in Germany are heat pumps; the vast majority of households use oil or gas boilers. Berlin wants newly installed systems to be at least 65 per cent powered by renewables from next year.

Greater success has come in countries where the financial incentives are clearer.

The gas price crisis in Europe last year helped trigger a “tipping point”, the European Heat Pump Association said: sales grew by 39 per cent in 2022 with almost 20mn pumps now installed in Europe and the UK.

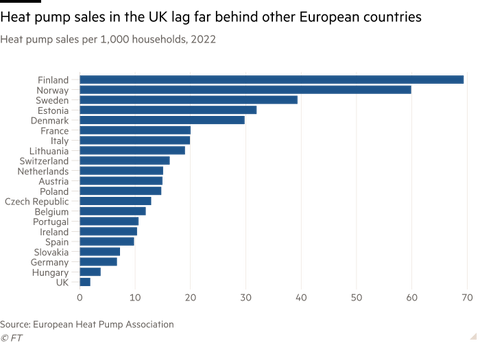

National rates vary hugely, generally depending on energy costs, existing heating stock and the mix of carrot and stick applied by governments.

Norway might have become rich on being a big oil and gas producer but the nation started moving away from oil-fired heating after the 1973 oil shock, and banned oil and paraffin for heating in 2020. With its vast hydropower reserves, it has shifted towards direct electric heating and heat pumps.

Climbing electricity prices last year boosted uptake, according to Rolf Hagemoen, secretary-general of the Norwegian Heat Pump Association, who recently installed one in his mountain cabin.

“It provides everything I need,” Hagemoen said. “I only use wood now if I want the cosiness.”

Poland was another leading adopter last year, with installed heat pumps doubling. Clean air rules as well as subsidies covering up to 90 per cent of the cost of boiler replacement have helped. As has solidarity with Ukraine.

“I didn’t want to fund Putin,” said Pawel Lachman, at Port PC, the Polish heat pump group, who installed a ground source heat pump after Russia invaded Georgia in 2008.

In Italy, tax credits worth up to 110 per cent of the cost of energy efficiency upgrades have boosted sales to be the seventh highest in Europe last year.

“In terms of comfort I prefer it now,” said father-of-three Federico Musazzi, whose landlord in Milan installed a ground source heat pump, although he adds that the relatively high cost of electricity in Italy limits savings.

Companies are starting to ramp up production to meet the rising demand. China’s Midea has laid out plans to grow in Europe by building a heat pump factory in Italy.

Not to be outdone, Germany’s Vaillant has pledged nearly €2bn to boost its business, including a new factory in Spain to more than double production capacity to 500,000 units a year. Bosch said it would invest more than €1bn to expand in Germany, Portugal and Sweden and build a new factory in Poland.

US-based Carrier Global is spending €12bn to acquire Viessmann, a German heating equipment group. Its chief executive David Gitlin told investors Europe was the “single most attractive market in the world” and he expected EU heat pump sales to triple to $15bn by 2027.

But the UK stands as out as a laggard. It has a poor ratio of electricity to gas prices, helping explain the weak interest, with only 1.9 heat pumps per 1,000 households sold last year — the least in Europe.

In Britain, electricity currently costs 30p per kWh compared with 8p per kWh for gas, under the price cap governing most energy bills. That is partly due to policy costs lumped on to electricity prices, which the government is looking to change.

“There’s a clear correlation between low electricity prices and high heat pump uptake,” said Charlotte Lee, at the UK’s Heat Pump Association. “It’s much easier to take a leap of faith if the decision makes financial sense.”

Savings can still be high. In Derbyshire, homeowner Steve Munn estimates he saved about £930 in just the first four months after installing a heat pump and solar panels and leasing an electric car. “We need to wean ourselves off gas,” he said.

Upfront costs vary but estimates suggest it costs around £7,000-£15,000 to buy and install an air-source heat pump in Britain. Suppliers including Octopus Energy are working to bring down costs, although there is debate over the extent they can fall.

“I don't think we’ll get huge economies of scale from the costs of making the technology,” said Carl Antzen, chief executive of equipment maker Worcester Bosch. “There are savings we can make in the time it takes to install it.”

Even there, the scope may be limited. “At the end of the day, this is a job done by people with their hands,” said Emma Bohan, general manager at IMS Heat Pumps, based near Sheffield.

There are also bureaucratic barriers in the UK even if costs fall. Homeowners in England need planning permission to put a heat pump less than one metre from the property boundary. “It’s enough to put off all but the most determined,” said Clementine Cowton, external affairs director at Octopus Energy.

In his quest to boost take up, Turner asked his installer, a sole trader, whether rising demand would mean he could employ another technician to do twice the amount of work. In return, the installer asked “where I’d get the apprentices, where the skills are?”

But Turner is pleased with the result. “It works a treat,” he said, dismissing as “myth” that houses need perfect insulation for a heat pump to work in effect.

“We have increased the size of the radiators, but not dramatically,” he said. “The temperature might be a bit less than you might want in a really cold snap, but we’ll just put on woolly jumpers.”

To learn more about photovoltaic power generation, please follow SOLARPARTS official website:

Twitter: Solarparts Instagram: Solarparts

Tumblr: Solarparts Pinterest: Solarparts

Facebook: Shenzhen Solarparts Inc

Email address: Philip@isolarparts.com

Homepage: www.isolarparts.com