https://www.pv-magazine-australia.com/2023/01/28/shining-a-light-on-supply-chains/

Weekend read: Shining a light on supply chains

The providers of quality assurance services have developed strategies to provide detailed insights into solar supply chains.

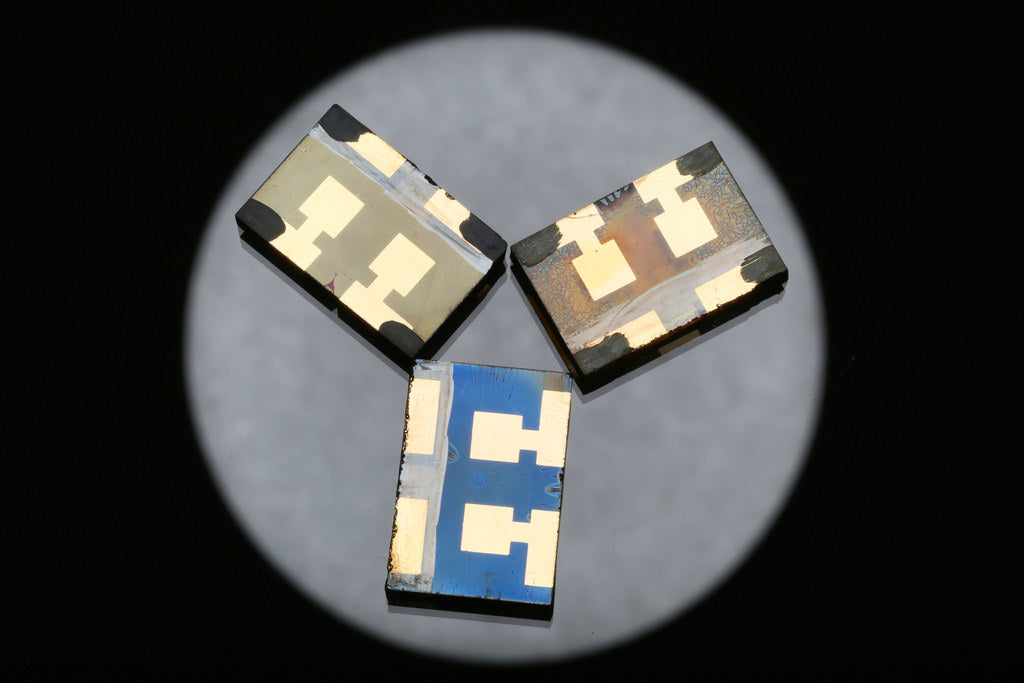

Photo: STS

From pv magazine ISSUE 01/23

Emphasis on supply-chain transparency has been a recurring theme through the last 18 months of pv magazine’s UP Initiative. Questions about material sourcing in solar and the alleged use of forced labor in Xinjiang prompted strict legislation in the United States. The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) was signed into law by President Joe Biden on Dec. 23, 2021, and was enforced from June 21, 2022. The act aims to prevent imports of goods made with forced labor and stop US companies from funding the responsible regimes.

The repercussions for solar, in particular module makers, are well known. Some 40% to 45% of the world’s polysilicon comes from China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region thanks to cheap electricity prices. US Customs and Border Protection enforces the forced labor act with an “entity list” of banned organisations. Since the introduction of the act, solar products on a gigawatt scale that do not meet traceability requirements have been detained at US ports; including 1,053 shipments seized between June 21 and Oct. 25, 2022.

Regulatory requirements

The risk for solar companies is significant, so supply chain auditing has rapidly advanced. Professional certification and auditing services have become popular, having accumulated decades of supply chain experience in industries such as automotive and electronics.

However, the provision of supply chain audits is a relatively new field and not all providers, including analysts, were forthcoming with information regarding processes, challenges, and the development of the services. Some also hold concerns that key relationships with the Chinese PV industry can be damaged by the discussion of politically sensitive issues.

“In the US, traceability is a question of legal compliance,” Mariya Stoyanova, director of supply chain sustainability services at technical advisory STS – which provides conformity assessments – tells pv magazine. “If you don’t have in place what is needed, you’re taking a risk, as your shipment may be stopped at the border. Traceability requirements are simply here to stay. You can’t say ‘no, we aren’t doing it.’ Once it became apparent that it was necessary to have a robust traceability system in place and a relationship with suppliers to be able to collect upstream supply chain documentation, companies started to prepare for it.”

She says it is always easier to achieve supply chain visibility if you’re an integrated manufacturer and you can control a certain portion of the supply chain. Auditors can face resistance from suppliers reluctant to share details of commercial pricing contracts or from less mature companies that lack internal traceability systems. As the sector evolves, however, traceability information is becoming more readily available.

“We had to essentially establish this relationship of trust because of the sensitive nature of key data,” says Stoyanova. “There was some natural hesitation in the beginning despite rigorous protocols in place for both the treatment of data and for who even has access to the data. But we built trust, with experience of tens of gigawatts of audits, and now we start to be in a good place.”

Auditing in action

US-based Clean Energy Associates (CEA) offers supply chain auditing and Joerg Althaus is the company’s director of engineering services, quality assurance, and environmental, social and corporate governance. He says getting auditing up and running was not easy for the solar industry because traceability-enabled procurement was lacking.

“The first step is to make sure a system is in place that allows us to go into an inventory or purchasing tool to see where factories are buying from, which is supply chain mapping, or establishing who are the suppliers to the suppliers,” he tells pv magazine. “That happens by making sure, on paper, that traceability is there by volume but also that it is documented. That’s where you can audit.”

However, Althaus says it becomes more complicated “when you go further upstream, where you could have multiple suppliers of raw material ending up in the same product, along with blending, which you can’t see in the end product.”

Althaus predicts auditing steps will go further upstream. “We all know you can’t go into all the factories upstream yet – that traceability is not there, but that still might come,” he says. “But it entails that everybody along this supply chain works together. Other industries have done that by electronic means and actually measuring volumes. But at the moment, we have made good steps.”

An example is supply-chain mapping via geolocation, using logistics as a factor to determine mining and logistics supply. Althaus gives the example of a polysilicon factory. Call that “location A,” he says. “And you know the distance to the mines around it and you know the logistics cost within China,” he adds. “With some data crunching, you can say: ‘If I’m buying from this factory, it is very unlikely that the raw material is coming from further away than local mines, or the other end of the country, because the logistics cost would put the product at three times more expensive.’”

Assurance levels

Stoyanova says her employer has varying levels of assurance – the lowest are an absence of reporting, or self-declaration. Higher assurance comes from verification of documents during audits on behalf of the buy side – “second party” audits.

“The next level of assurance would be when we are presented with documents to establish links between different upper-tier suppliers,” she says. “For example, purchase orders, invoices, or bills of lading [issued by goods carriers to shippers], and, more rarely, contracts, because they can be very sensitive. But purchase orders usually do the trick. That would be the ‘product traceability documented’ level. The highest level of assurance for us, which we call ‘product traceability verified,’ is when you’re able to link the batch numbers and establish traceability between input and output.”

Stoyanova adds that this process involves checking “the production records in the MES [manufacturing execution systems]. For example, we trace the cell batch numbers that were used for the production of a certain shipment of modules. We then look for the corresponding wafer batch numbers, ingot brick numbers, polysilicon batch numbers and link it with the unique identifiers provided for the corresponding silicon metal and, if available, quartzite. We’re now usually able to get this verification, at least until polysilicon.”

Stoyanova says auditing speed has increased. “With good working relationships, it’s become quicker. There was one case that took us a few months with supply chain mapping. We went to the module side, wafer side, ingot side, and Covid-19 complications made it harder. But now manufacturers know what they need to collect and we know how to do it efficiently and the results are, we’re able to go deeper into the supply chain.”

Chain reactions

The benefits of truly reliable, certified supply chains extend beyond meeting regulations. And Althaus argues that improvements in traceability can have multiple positive outcomes.

A seller’s market

In the solar industry, sellers control the power dynamic for buyers. This unique situation is the opposite of what the automotive industry experiences, where large buyers compel suppliers to follow their traceability and sourcing requirements.

“I’ve been in this industry for 20 years and have seen shortages in silicon, shortages in back sheets, shortages of inverters, and so on. Solar has seen multiple supply chain issues over the years, leading to fundamental company breakdowns,” he says. “Part of our offering to customers and suppliers is establishing partnerships and establishing quality. Knowing, for example, that a supplier can deliver on time and volume for a project.”

While there is a focus on polysilicon in the solar industry, buyers and asset owners benefit from knowing the exact bill of materials for their products, Althaus says. “We’re blessed in solar because the bill of materials in solar is quite restricted,” he explains. “You really have only some 10 to 15 components in a PV module and the asset owner knowing exactly the bill of materials for each product in the field has multiple benefits, from tracing failures to end-of-life recycling.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

<