https://www.pv-magazine-australia.com/2023/05/13/weekend-read-indonesias-race-to-net-zero/

Indonesia’s race to net zero

PLN’s progress on replacing small diesel generators has been slow, despite the completion of some PV projects, including this one in northern Sumatra.

Image: The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Indonesia

From pv magazine ISSUE 05/23

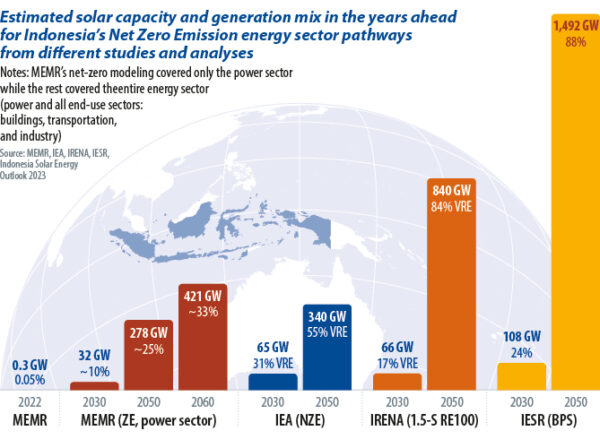

In 2021, the Indonesian government announced a goal to achieve net zero emissions by 2060 at the latest. The pivotal role to be played by solar has been confirmed by the country’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), the IESR, the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). As the IESR reported in its “Indonesia Solar Energy Outlook 2023” report, PV deployment has fallen far short of decarbonisation requirements.

The world’s fourth-most populous nation – with 275 million people – is Southeast Asia’s biggest economy and expected to be the world’s seventh largest by 2030. Being the world’s 15th largest nation by surface area contributes to a technical solar generation capacity potential of 3 terawatts-peak (TWp) to 20 terawatts-peak, depending on land use. Around 1.5 TWp of that potential, occupying 2.5% of Indonesia’s land, could support a zero-emission energy system by 2050, according to IESR’s study, titled “Deep decarbonisation of Indonesia’s energy system.”

Cost-competitiveness, modularity, and availability ensures solar would be the leading electricity source in most Indonesian net-zero economy models. Solar and, to a lesser extent, wind will supply 55% of Indonesia’s electricity in mid-century, according to an IEA model consistent with keeping the global temperature rise this century capped at 1.5 C. IRENA estimates 800 GW to 840 GW of solar could supply 54% to 62% of Indonesia’s electricity by 2050. Both scenarios would require greater power system flexibility, expansion of electricity transmission infrastructure, inter-island interconnections, and energy storage.

Current progress

Energy ministry data, however, shows Indonesia had deployed only 270 MWp of solar by the end of December, around 0.01% of the lowest technical potential estimate. Policy and regulatory uncertainty combine with a lack of planning and implementation in an electricity market dominated by state utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), which generates, transmits, and distributes power.

For example, although PLN’s 10-year power development plan – to 2030 – envisages 4.7 GW of solar, including 3.9 GW operational by 2025, there were only eight projects, with a total generation capacity of 600 MW, in the pipeline last year, all of them tendered before the power plan was drafted.

PLN has also tendered the first phase of a plan announced last year to replace 500 MW of small diesel plants in remote locations but unfavourable results mean the procurement round will be held again, delaying the project. The utility has been criticised for a lack of transparent auction scheduling, leading to market uncertainty.

Bright spots

There have been successes, though. Solar power purchase agreement (PPA) prices fell 76% from 2015 to 2020, from USD 0.25/kWh to USD 0.058/kWh. The decline is 84% (to less than USD 0.04/kWh) when including two record-low bids attracted by PLN subsidiary Indonesia Power’s equity partner selection exercise for floating solar projects in Singkarak and Saguling which have a total generation capacity of 110 MW. PLN companies this year issued invites to tender for a 100 MW floating solar project at Karangkates dam plus the second phase of its equity partner selection for utility scale solar and wind facilities.

Rooftop solar has enjoyed modest growth since net metering regulations were established in 2018 but PLN-imposed restrictions have slowed installations. Energy minister Arifin Tasrif in 2021 drafted a regulation that specified each kilowatt-hour exported to the grid by net-metered solar owners would earn a full kilowatt-hour off electricity bills, up from a 65% credit being paid by PLN.

The energy minister also streamlined the net metering application process but PLN, citing grid capacity concerns, chose not to implement the new system and subsequently limited net-metered solar system capacity to 10% to 15% of the prosumer’s electricity connection.

With fewer net-metered customers arriving in 2022 than in previous years, Jakarta is attempting to find a middle ground to assuage PLN’s capacity fears and suggestions include abolishing net metering and applying a quota to applications. While industrial solar could benefit from any removal of capacity limits, home solar and small business use is expected to suffer from an extended payback period for net-metered systems.

The Indonesian government and PLN still have a lot of work to do to make solar-powered decarbonisation successful. Momentum was generated by last year’s presidency of the G20 group of economies as well as Indonesia’s signing of a Just Energy Transition Partnership with a slew of multilateral lenders, to fund a shift from coal to clean energy.

The early retirement of coal and widespread adoption of solar are critical to the nation’s aim of limiting peak power sector emissions to 290 megatons of CO2 by 2030 and having renewables supply 34% of electricity this decade.

Through its energy chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations this year, Indonesia can strengthen the role of solar power in the context of regional energy security through collaboration in the power system and beyond, including promoting the PV supply chain in the region. While the path is winding, the route to clean, affordable, and equitable energy – with solar as its backbone – is clear.

About the authors: Daniel Kurniawan is a solar policy analyst at the IESR and has been involved in solar-related consultancy with government agencies, local, and international counterparts. He was formerly a solar cell researcher and trained in materials science.

About the authors: Daniel Kurniawan is a solar policy analyst at the IESR and has been involved in solar-related consultancy with government agencies, local, and international counterparts. He was formerly a solar cell researcher and trained in materials science.

Fabby Tumiwa is executive director and a founding member of IESR and chairman of the Indonesian Solar Energy Association. For more than 20 years, he has worked on a range of energy policies and regulations.

Fabby Tumiwa is executive director and a founding member of IESR and chairman of the Indonesian Solar Energy Association. For more than 20 years, he has worked on a range of energy policies and regulations.

This copy was amended to indicate Indonesia’s technical solar potential should be measured in terrawatts-peak (TWp) rather than petawatts-peak (PWp) as indicated in the print edition.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

<