https://www.pv-magazine-australia.com/2023/04/01/weekend-read-a-moral-trilemma/

A moral trilemma

Photo: NEXTracker

From pv magazine ISSUE 03/23

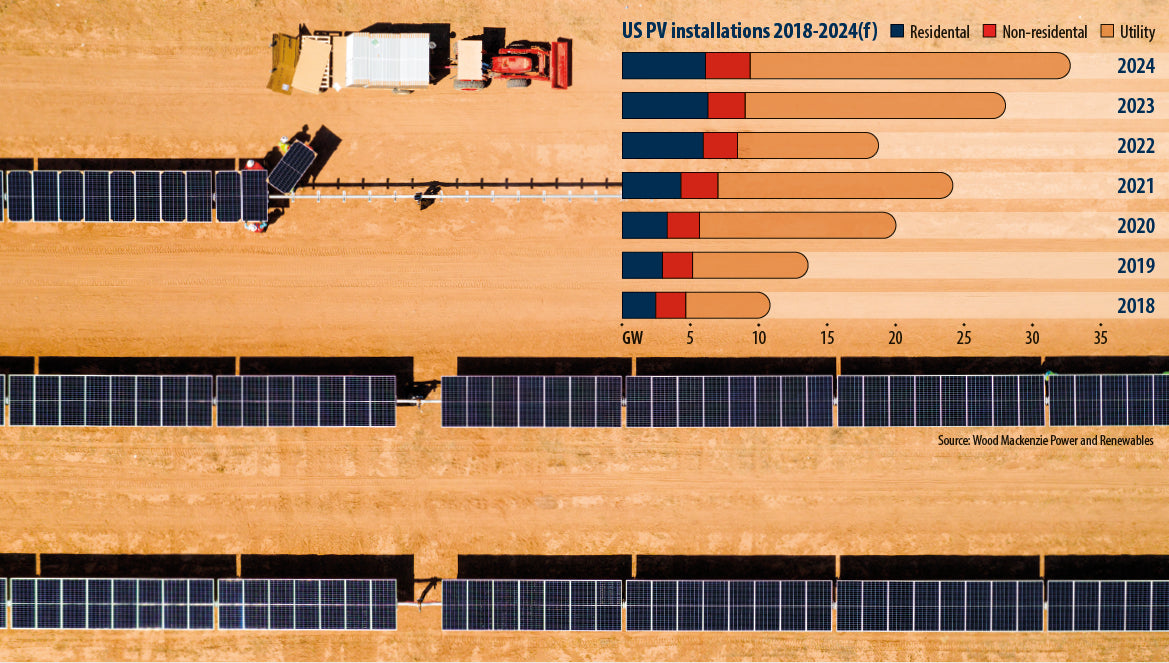

The numbers don’t make for great reading. According to energy analyst Wood Mackenzie, the US solar market declined 16%, year on year, in 2022. Some 20.2 GW of solar was installed in a market that should be undergoing supercharged expansion on the back of generous Inflation Reduction Act subsidies.

By contrast, the European solar marketplace expanded 47% to 41.4 GW last year, according to SolarPower Europe. China’s National Energy Administration also reported exceptional growth in 2022, with 87.4 GW of solar completed, for year-on-year expansion of 60.3%.

There are, however, glimmers of hope for solar in the US. Utility scale deployment rallied in the fourth quarter, achieving 4.3 GW and 11.8 GW for the year – a decline on 2021 but not as catastrophic as some had feared.

“Q4 had a 67% higher buildout compared to Q3, mainly driven by module shipment releases by CBP [US Customs and Border Protection],” says Sylvia Leyva Martinez, a senior research analyst with WoodMac. While detailed information is lacking, investment bank Roth Capital Partners announced, on Feb. 5, that JinkoSolar “continues to see modestly sized, steady releases” of modules detained by US border officials, while Longi is also seeing “modest” module releases. The bank noted releases in some cases were being delayed as CBP lacks sufficient staff to assess and release module shipments in a timely fashion.

Key legislation

Border module detentions are the result of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) signed into law by US President Joe Biden on Dec. 23, 2021. The legislation passed both houses of Congress with only one dissenting vote. The UFLPA restricts the import of goods, “mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China” – due to credible accusations of the use of forced labor involving the Uyghur ethnic minority in the region.

In November 2022, Reuters reported more than 1,000 solar energy component shipments – valued at hundreds of millions of dollars – had been blocked in US ports under UFLPA enforcement. Roughly 4 GW of modules may have been prevented from entering the US last year, according to Philip Shen, MD at Roth Capital, as published in a research note. Some are likely to have been held back by manufacturers, for fear of being seized.

The UFLPA includes a “rebuttable presumption,” ensuring goods from Xinjiang – home to almost half the global solar polysilicon supply chain – are presumed to be made with forced labor. The act places the burden of proof on buyers to show goods have no connection to such practices.

To comply with the UFLPA, companies must provide comprehensive supply chain mapping, a list of all workers, and proof they were not subject to conditions typical of forced labor. “The origins of components and materials used in PV products are not ascertained through a direct identification process,” market intelligence company TrendForce noted in a recent report. “Instead, regulatory agencies often have to rely on product manufacturers and importers to provide supply chain information and sourcing certification.”

New threats

UFLPA-related supply constraints are only the latest in a string of trade measures affecting US imports of Chinese modules. The unencumbered supply of solar components has faced a “trade trilemma” for years. The Hoshine withhold-release order (WRO), and the Auxin Solar-instigated Section 201 anti-dumping tariff case (see box below) represent two other threats to the steady supply of solar goods. Those measures began affecting the market in 2021 and 2022, respectively, meaning supply disruption has been a constant for more than two years.

Dumping and countervailing duties

The module supply disruption caused by the Hoshine withhold-release order and the UFLPA has been accompanied by US government anti-dumping proceedings. Allegations of the dumping of Asian-made solar modules were made in a petition from Auxin Solar, a module assembler with operations in California. The petition alleged four Southeast Asian countries – Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Malaysia – were harbouring Chinese-made goods in violation of anti-circumvention laws. Tariffs on solar goods, enforced under anti-circumvention laws, have historically exceeded 50% to 250%. The uncertainty was temporarily lifted when President Biden, on June 5, placed a 24-month moratorium on solar tariffs on the four nations. The tariff exemption applies to modules imported before June 6, 2024, and installed before December 2024. The moratorium, though, is now under threat. In late January, a small coalition of Democrat and Republican Congress members filed legislation to repeal it. “The Biden administration found, in its own investigation, that China is evading US tariffs on solar imports but has paused action on this matter, which is unacceptable,” said Congressman Dan Kildee, a leading voice in the coalition. Repeal would “help America’s domestic solar manufacturing industry grow to meet our nation’s energy needs,” he said. The repeal petition will expire on March 28, if not passed.

Brian Lynch, director of solar sales at LG Electronics USA, warned pv magazine USA of disrupted supply in 2021. “[If] you’re buying a solar module in the foreseeable future, all of these events will likely impact you, directly or indirectly,” he said.

In June 2021, US Customs and Border Protection released a WRO on the Hoshine Silicon Industry company, a major industrial polysilicon company in Xinjiang. The action was taken under Section 1307 of the Tariff Act, which prohibits the import of merchandise mined, produced, or manufactured – wholly or in part – in any foreign country by forced or indentured labor, including forced child labor. Such goods are subject to exclusion and seizure and may lead to criminal investigation.

Most of the solar imports detained under Section 1307 were held by customs for eight months or more, with major releases announced in February 2022. Shipments containing 100 MW or more of Longi and Trina solar modules were released at that time. Then, as supply pressures from the WRO began to lift, the UFLPA – with higher traceability standards and its “rebuttable presumption” – was introduced.

Forced labor

While solar is undoubtedly a good thing, and rapidly emerging as the key renewable energy for the energy transition and global economy, growth cannot come at the expense of minority populations, environmental sustainability, and human rights. As the industry expands, it can be argued, the maintenance of solar’s social license becomes increasingly important.

Multiple independent investigations have been conducted and published since 2020 into the extent to which forced labor practices have been used in Xinjiang. The most extensive was published in 2021 by Sheffield Hallam University’s Laura T Murphy and Nyrola Elimä.

The “In Broad Daylight, Uyghur Forced Labor and Global Supply Chains” report documented so-called “surplus labor” and “labor transfer” programs announced by Chinese officials and in official media, regarding the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It detailed the expansion of the production of “non-ferrous metals, polysilicon, and mono- and polycrystalline wafers” in the region – an aim targeted by the regional government. Regarding solar, non-ferrous metals means metallurgical-grade silicon, or silicon metal, the feedstock for polysilicon production. The report noted various subsidies which, together with cheap energy and raw materials, make the region attractive to solar feedstock suppliers.

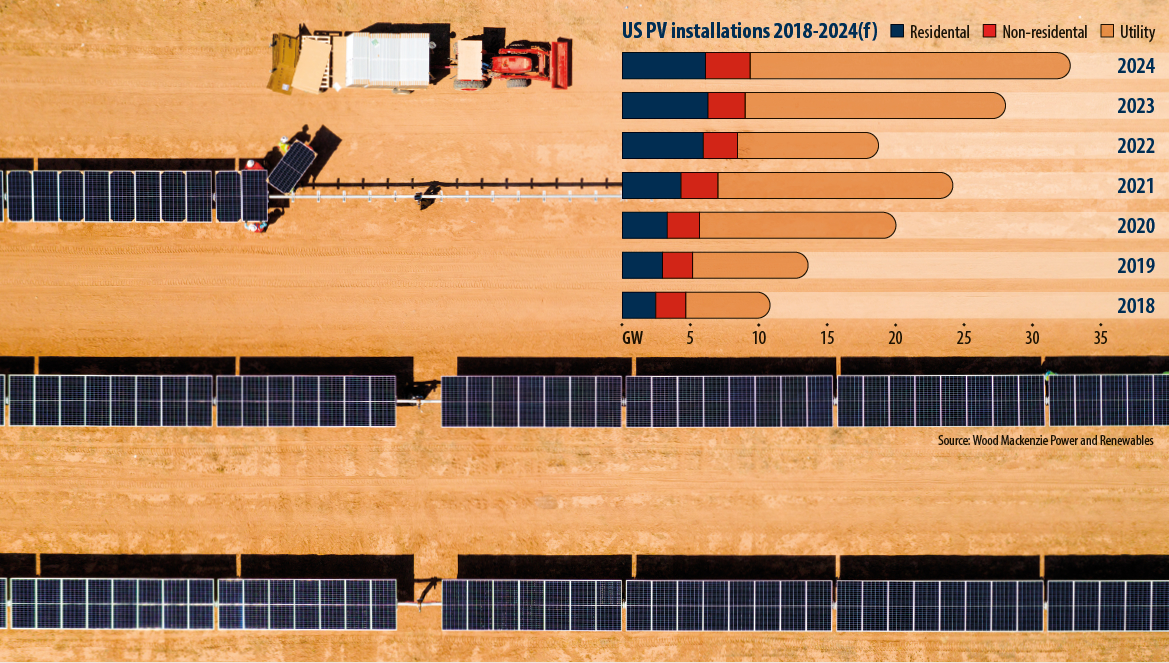

Investigations, and the publication of guidance for the PV industry, have continued since the Sheffield report. In January 2022, US-based asset management company Eventide published “Eradicating Forced Labor from Solar Supply Chains: Eventide’s Approach.” The asset manager is mulling PV investment, says Eventide analyst Reginald Smith, because of its social and environmental benefits. However, the company was troubled by reports of forced labor.

“We wanted to be ‘solutionaries,’” explained Smith during a recent pv magazine webinar, which is to say, solution-focused missionaries. “So we set out to describe a market-based action plan to progressively push forced labor out of the solar supply chain.” The result was methodologies in the report for understanding the “complicated” solar supply chain – Smith’s words – and whether it is “tainted” with forced labor.

The difficulties in ensuring an “untainted” supply chain, according to Eventide, stem from problems tracing the provenance of materials in a solar module. Metallurgical-grade silicon or polysilicon “tainted” by Xinjiang provenance can be blended with other sources in ingot and wafer production, Eventide argues. Smith adds, solar companies can establish and operate supply chains outside Xinjiang, specifically for the US market, while continuing to operate in the region.

“Solar energy buyers are still doing business with those that are involved in the oppression of the Uyghur people,” says Smith. The crux of the matter, the analyst concludes, is investor dollars can be put towards companies with supply chains outside Xinjiang – to the right of Eventide’s “Bifurcation Matrix” – according to the “glide path” the group sets out, below.

Investor impact

The extent to which such actions will affect the situation in Xinjiang is unclear. “The US is not that important a solar market,” says Jenny Chase, head of solar at clean power analyst BloombergNEF. “It is less than a quarter of the Chinese domestic market.” While the Sheffield report and others note Chinese manufacturers supply “over 95%” of global solar wafers, there is sufficient non-Xinjiang polysilicon for the US market.

“There’s enough silicon from outside China for 40 GW [of installations] plus whatever First Solar makes,” says Chase, referring to the US solar manufacturer. First Solar produces cadmium telluride thin-film modules, hermetically sealed from the crystalline silicon supply chain. BloombergNEF forecasts the US market will install slightly less than 30 GW of solar this year.

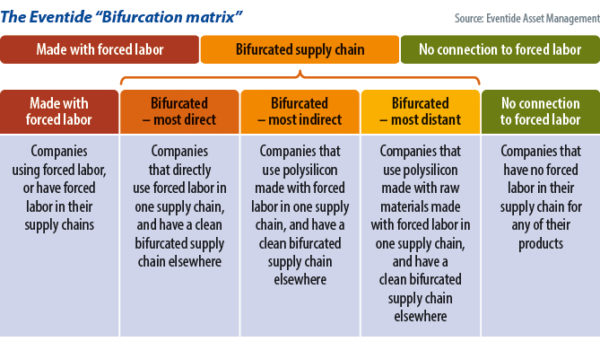

Polysilicon supply

Polysilicon analyst Johannes Bernreuter, head of Bernreuter Research, says around 12% of global solar polysilicon production came from outside China in 2022 – an historically low level but still 115,000 metric tons (MT) – enough for 45 GW of solar wafers. These producers – Germany’s Wacker, Hemlock Semiconductor, fellow South Korean outfit OCI, and Norway’s REC Silicon – are all expanding capacity or refurbishing mothballed lines – for 65,000 metric tons (MT) more output, sufficient for 25 GW of wafers.

While it will take time for this capacity to come online, Bernreuter notes the “big, fully integrated manufacturers” have put in place more detailed material tracking to verify the non-Xinjiang nature of supply. “Manufacturers are able to track the material flow in their factories, from the incoming polysilicon through to the finished solar module with a, so-called, manufacturing execution system,” says Bernreuter.

As to the silicon metal – a term Bernreuter prefers to metallurgical-grade silicon as the latter “almost breaks your tongue” – the situation is a little more nuanced. It appears non-Chinese producers have made efforts to move supply chains away from Xinjiang, and some from China altogether.

Bernreuter finds Hemlock’s claim it sources silicon metal from North and South America “credible,” and notes OCI “stated they have changed silicon metal sources to other regions in the world and don’t procure silicon metal from Xinjiang any more.” For Wacker, Bernreuter reports that while the company was a Hoshine customer from 2016 to 2020, that detail “has disappeared from the 2021 annual report.” The company has acknowledged procuring silicon metal from China without providing more details. “The fact that the name of Wacker has disappeared from the Hoshine report would point to that they have stopped procuring from Xinjiang but I have no positive evidence of that,” adds Bernreuter.

Adjusted supply chains

That the solar supply chain is adjusting to account for the UFLPA and other measures should come as no surprise – a clear signal was sent from the US marketplace and manufacturers responded. BloombergNEF’s Chase concludes “the major companies have now figured out what paperwork they need to file,” to clear US customs.

That supply chains and traceability are evolving as required by the UFLPA is a positive development and evidenced by reports of module releases and the uptick in US installations in the fourth quarter. Bifurcated supply chains, as denoted by Eventide, still exist, although so too do those “untainted” by forced labor accusations.

Slightly more than 20 GW of new solar in 2022 is below the 30 GW required annually under the Biden administration’s decarbonisation goals – modelled by the US Department of Energy’s Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO). And it is well short of the “up to 60 GW” required annually between 2025 and 2030.

The SETO modelling is based on solar continuing to achieve “aggressive cost reductions,” on the back of supportive policy measures, with demand driven by “large-scale electrification” of the US economy. Realignment of the solar supply chain to add capacity outside Xinjiang, along with the soft costs associated with enhanced traceability, will add to PV’s price. “It won’t be cheap but since when has the US ever been cheap?” asks Chase.

Whether the UFLPA and other measures will have a meaningful impact on alleged forced labor remains unclear. While Bernreuter points to major polysilicon capacity growth outside the region, the industry there continues. “There is a lot of new capacity coming up in Inner Mongolia but also sizeable new projects in Xinjiang,” says the analyst.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

<